Pathway to resilience n ° 3: Promoting the technical and energy autonomy of farms

- 2020-02-01 09:34:30.0

- 14600

- farm, technical autonomy

Current agricultural production is based on a complex technical system and high consumption of fossil fuels. This lack of autonomy is a vulnerability in a context of economic and energy constraints. The development of a manufacturing network for low-tech agricultural tools and local energy sources is an essential factor of resilience at the territorial level.

State of Affairs

More tractors than farmers

Productivity gains, loss of autonomy

Motorization is one of the pillars of modern agricultural production . During the second half of the twentieth century, many towed tools and self-propelled machines were developed and marketed to carry out specialized agricultural work: plowing, sowing, spreading, pumping and irrigation, harvesting ... The power released by heat engines allowed a reduction in the arduousness of the work, and above all, a gigantic leap in productivity . The area of cereals that can be cultivated by a farmer equipped with modern machinery now exceeds one hundred hectares, where a farmer with only manual tools can hardly cultivate more than one hectare.

Left: Harvester powered by a 33-horsepower hitch in 1902 in Washington, USA. Right: Modern, mid-size combine harvester producing 300 horsepower. Crédits : Robert N., domaine public ; PRA, CC BY-SA, Wikimedia Commons.

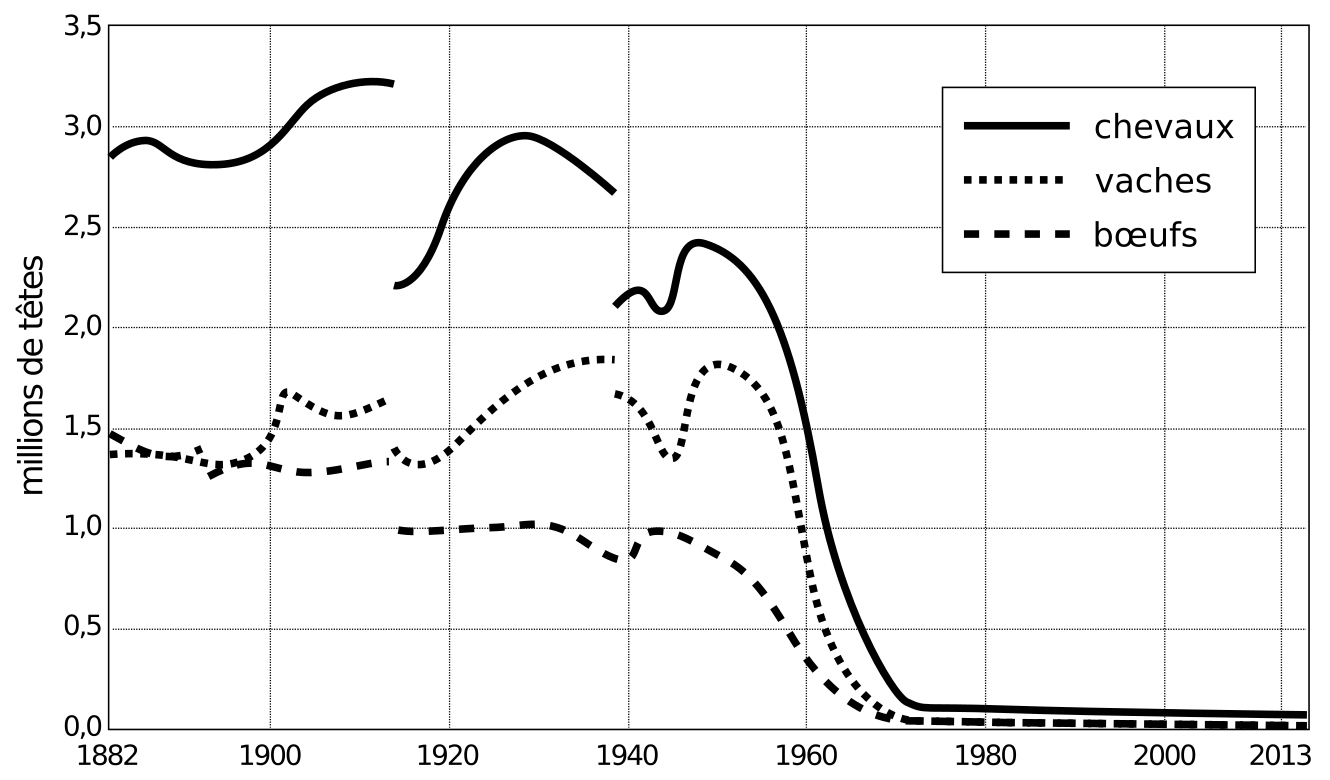

The significant gain in competitiveness associated with motorization, as well as the political and financial incentives for productivism, led to the rapid development of these machines, and caused a sudden substitution of tractors for draft animals ( Figure 17 ). The fodder surfaces intended for them have thus been freed up and largely reallocated to the development of animal production (meat, milk, eggs). A major change of use since, for example, oats cultivated in 1929 in France to feed draft animals represented 3.5 million hectares, or one third of the cereal area at the time .

Figure 17 : Evolution of the number of draft animals in France since 1882. The motorization operated at the end of the Second World War led to a rapid abandonment of animal traction. Source : Les Greniers d’Abondance, Harchaoui et Chatzimpiros (2018a).

Today in France there are more tractors than farmers . The immediate corollary of the increase in productivity associated with motorization is a reduction in the need for labor. The arrival of tractors therefore precipitated the rural exodus that began in the 19th century, leading us to the unprecedented situation detailed in the previous chapter: just over 1% of the population today produces food for the 99% remaining .

However, this increase in productivity has several important setbacks:

- in less than a century, farms have gone from a situation of energy autonomy (draft animals were fed by crops and meadows) to a almost total dependence on fossil fuels ;

- most farmers are dependent on a complex and specialized industrial system to maintain and renew their equipment, while most of their tools were easily repairable on or around the farm a few decades ago;

- this modern equipment has a high cost - 20% of operating expenses on average in 2013 - and requires heavy debt;

- Their amortization is often based on the expansion of exploitation and the intensification of agricultural practices, resulting in the homogenization of landscapes. This in turn exacerbates several threats to the food system: decline of wild and cultivated biodiversity, soil degradation and accelerated erosion.

Concentration and complexity

The widespread motorization of agriculture and the deployment of sophisticated technologies have therefore on the whole greatly reduced the operating autonomy of farms . This trend is strengthening: the majority of financing and innovations are now fueling power and productivity gains.

Equipment suppliers have also undergone significant concentration in recent years. Tractors, for example, which have become essential for most agricultural work, no longer have any French manufacturer since the takeover of Renault Agriculture by the Claas group in 2003. Four large foreign industrial groups (AGCO, Claas , Kubota and YTO) produce them nationally, but their assembly plants depend on vast networks of suppliers and subcontractors in France and abroad. This organization is based on the fluidity of national and cross-border trade. For other agricultural tools and machines (plows, harrows, seeders, spreaders, livestock equipment, etc.), the sector is less centralized and there are around 200 French companies, sometimes close to crafts, which produce or import them. on the territory. In addition, there are around 3,300 craft businesses providing maintenance and repair services.

Finally, free trade has fostered the division and hyper-specialization of construction chains . Recently, in anticipation of a "hard" Brexit, an article in the Guardian took the example of a Mini crankshaft to illustrate this phenomenon: the mold is produced in France and then sent to the BMW factory in Warwickshire (west of France). 'England) to forge the part, which is then sent to Munich to be integrated into the engine, before leaving for Oxford where the engine and its crankshaft are integrated into the automobile. If it is sold on the continent, this one piece will have crossed the Channel four times.

Links to resilience ?

Associated threats : depletion of energy and mining resources, economic and political instability

The high complexity of supply chains points to the disruption that could affect the agricultural equipment industry if trade and trade relations deteriorate. In the current uncertain context, the characteristics of modern agricultural machinery become a vulnerability .

Farms were until recently "modular" parts of the food system, that is, they could operate with a certain level of autonomy and independence . Several testimonies from peasant families who went through the Second World War relate the adaptability of their farm in an economic and social context that has yet radically changed: economic crisis, loss of male labor, requisitions, looting, generalization of barter and black market.

Soviet-made tractor abandoned in Cuba. During the "special period" Cuba saw itself deprived of most of its imports of agricultural machinery and petroleum products. Many farmers then abandoned their motorized tools in favor of animal traction. Crédits : Pixabay.

Conventional operations are now heavily dependent on the petroleum industry and their equipment suppliers. The complexity of manufacturing and maintaining our agricultural machinery is a major vulnerability factor . The risk of supply disruption should be considered in the event of a major economic crisis, leading to the closure of certain factories or the bankruptcy of a key supplier. This applies in particular to maintenance and repair parts.

The dependence of our agricultural machinery on oil is perhaps the most obvious risk factor. However, it is not necessarily the most difficult to manage in the event of an oil shock. Tractors and other agricultural machinery consume less than 5% of refined petroleum products in France. It can be assumed that in the event of a constrained nationwide supply, local authorities would have some leeway to secure the needs of farmers. This is what happened during the 1973 oil shock: the agricultural sector was excluded from the rationing policies instituted in the United States and in several European countries. However, a distinction must be made here between the physical availability of fuels and their economic accessibility. The most dependent farms will be economically weakened in the event of an oil shock, and may be financially unable to ensure all or part of their production .

Objectives

Today in France there is very little research and development on tools allowing a certain degree of autonomy, adapted to resource-saving agricultural practices, and which can be easily repaired . The specifications for such tools would imply simple manufacture, based as much as possible on the resources and knowledge available at a local scale, while offering real improvements in ergonomics and productivity. These would be adaptive tools, which can be freely shared, repaired and modified according to individual needs. They would be similar in this to "low technologies" or low tech . This research is to be promoted by public actors.

The existence of a local and dynamic sector of construction and maintenance of agricultural equipment is an important factor of resilience of the territory . Depending on the complexity of the equipment produced - everyday tools, specialized equipment, heavy machinery - different levels of networking must be considered, from the inter-municipal to regional, or even national, scale.

The energy autonomy of farms is also a key resilience factor . It can be improved in two ways:

- by limiting needs , in particular for tillage, thanks to various agronomic practices such as those developed by conservation agriculture,;

- by producing energy directly on the farm , the simplest then being to devote part of the land to the production of biomass which will be converted into mechanical energy for agricultural work. Two possibilities then exist: feeding draft animals with this biomass and developing animal traction, or transforming this biomass into biofuels (pure oils, biodiesel, bioethanol, biogas, etc.). From an energy point of view, these two conversion methods offer a fairly similar efficiency (respectively 8-10% and 12-15%). They have different advantages and disadvantages and each require specific infrastructures and organization.

Actionnable Levers

LEVER 1 : Sensitize farmers to technical autonomy In partnership with local artisans and businesses or with professional training organizations such as the Atelier Paysan, raise awareness among farmers of the importance of technological sovereignty. Organize meetings between farmers and local professionals around agricultural equipment and the collective resolution of targeted technical issues.

No-till seed drill designed and built by farmers with the help of Atelier Paysan. L’Atelier Paysan is a cooperative (SCIC) for the self-construction of agricultural equipment pursuing an approach of reappropriation of peasant knowledge and empowerment in the field of agricultural equipment. They bring together a variety of expertise with the aim of promoting artisanal inventions, developing with users new adapted technical solutions, and making this knowledge free and accessible through "open source" documentation and training in self-construction. Communities can organize training of this type in partnership with rural development organizations and thus facilitate the emergence of a local network for building tools. Crédits : l’Atelier Paysan, CC BY-NC-SA.

LEVER 2 : Promote the development of a local network of craftsmen-builders of agricultural tools

Provide premises to accommodate structures for the design / manufacture / repair of tools and agricultural machinery. A "house of peasant techniques" housing associations and / or professional mechanics can be developed at the level of the department.

Rely on the local skills of the industrial, economic fabric, possible technopoles, "economy", "innovation" "circular economy" services of communities to transfer skills between areas of activity. Adapting economic aid mechanisms, calls for projects from local authorities for the agricultural sector or promoting already existing financing (Regions, European funds) to farmers to bring about projects.

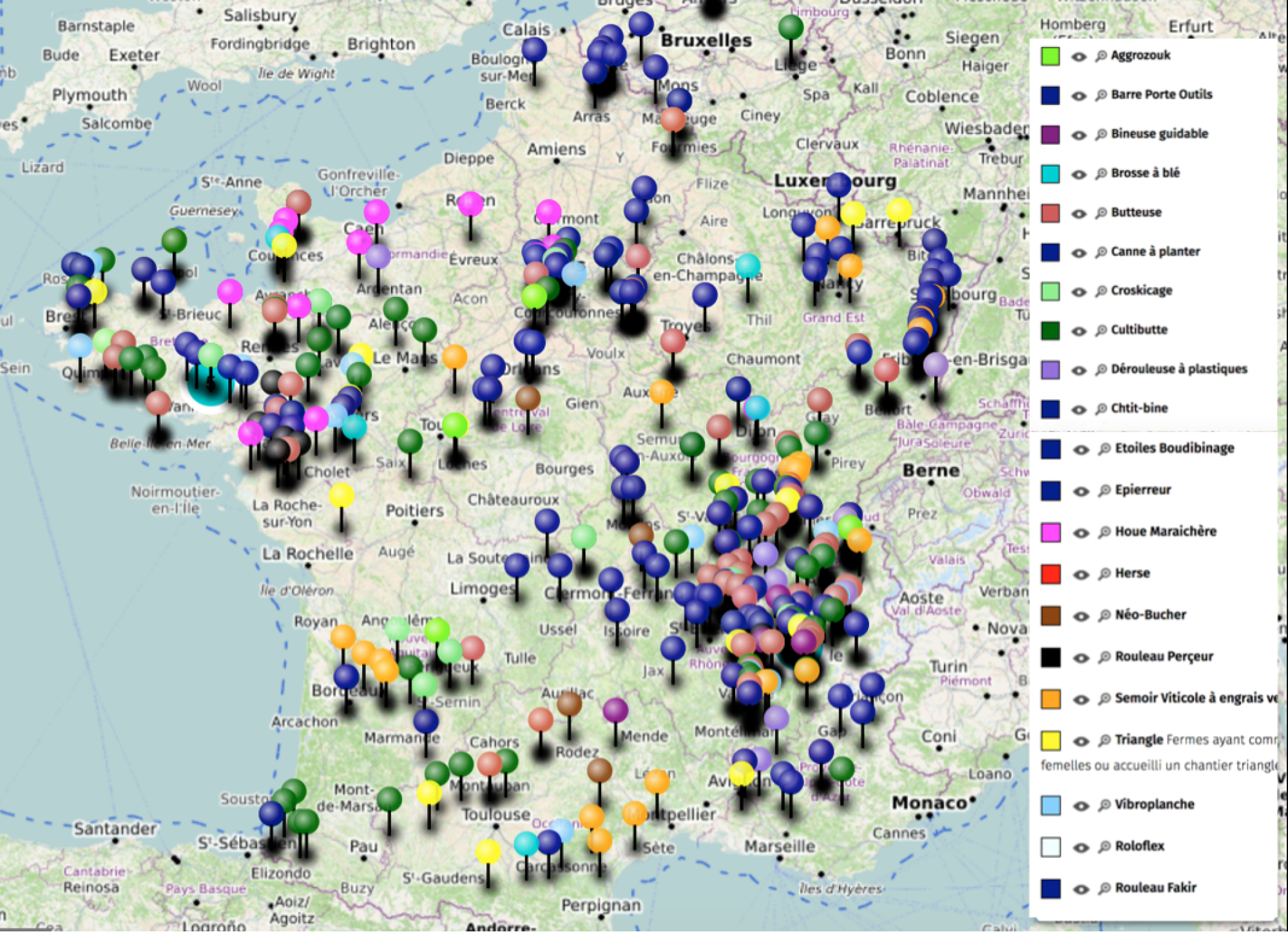

Map of France of self-builders of agricultural tools, provided by the Atelier Paysan.

LEVER 3 : Develop the pooling of agricultural equipment by supporting cooperatives for the use of agricultural equipment (CUMA)

Identify the needs shared by several farmers in the territory.

Provide financial support or support calls for projects - for example within the framework of the PCAE from the regions - to acquire the equipment, if possible by calling on the local sector for its manufacture.

Promote the maintenance or construction of a workshop hangar.

The hangar-workshop offers a number of services to a CUMA: the equipment is sheltered, gathered in a fixed place providing all the tools necessary for its maintenance, and the development of the CUMA is not restricted by the lack of space at the operators. Crédits : © Entraid.

LEVER 4 : Train farmers in energy efficient practices

Make farmers aware of how to control their energy consumption beyond the sole economic constraint. Fossil energy expenditure amounts on average only to 5% of the total current costs of farms, even though they constitute a crucial production factor.

Organize training, in partnership with the competent bodies, on energy-saving agricultural practices such as simplified cultivation techniques. Provide technical or financial support to volunteer farms to change their practices, in particular for the manufacture or purchase of specialized equipment.

LEVER 5 : Encourage self-production of energy in the territory

Support and accompany self-production energy projects based on local resources such as animal traction, biogas or biofuels. For the latter, the production of “pure fuel oil” - which can be used as such in diesel engines - is a route which benefits both from good efficiency and from an uncomplicated manufacturing process that can be carried out on a small scale. (simple pressing of oil seeds such as rapeseed or sunflower). Local sectors of second-generation biofuels, derived from crop residues (such as cereal straw) are being studied and could contribute to the region's energy autonomy. The agronomic importance of these resources for soil fertility (supply of organic matter) is however likely to lead to conflicts of use which would reduce their energy potential.

Help structure the sectors and build the necessary infrastructure.

In Saint-Gouéno (Côtes-d´Armor), farmers gathered to create the CUMA Ménergol and an oil mill for processing locally produced rapeseed. The oil obtained is used in particular as fuel for members' tractors. The community of municipalities of Mené joined in the support and financing of the project. Crédits : © Union Démocratique Bretonne

Side Benefits

Knowledge sharing and mutual aid are effective means of forging lasting human relations, in territories that are sometimes geographically landlocked or isolated.

The pooling of tools and knowledge, as well as empowerment for maintenance and repair, is a significant source of savings for farmers.

Obstacles

Unambiguous vision of innovation

Policies for economic development and aid for innovation in communities (region, EPCI) may be in contradiction with the guidelines for the development of tools and innovative knowledge known as "low tech". Typical “start-up”, “high tech” projects, based on patents and industrial property and dependent on material and energy abundance, are still often considered to be good “in themselves”, regardless of their relevance to -views contemporary issues.

Depreciation of investments

Operators are sometimes heavily indebted for the purchase of new and high-tech equipment, which they have to amortize over several years by maintaining certain production techniques.

Indicators

- Number of companies and craftsmen specializing in agricultural equipment in the territory

- Possibility (human and technical resources) for the farmers of the territory to build, repair or modify their tools

- Level of energy autonomy of farms